015: Rice as self. Or not?

Re-examining what we think about rice and identity

Emiko Ohnuki-Tierney’s 1993 work on Japanese identity “Rice as Self” is an insightful text on Japanese culture. It is also a wonderful example of two things: a book that goes obsessively deep into a single topic and a something written at a very specific time in history. Ohnuki-Tierney completed most of the manuscript* in the early 1990s, exactly when Japan’s economic bubble was about to collapse. The project of examining Japanese identity has long continued but there is something pleasant about time travelling to such an important period and examining some important assumptions. As she outlines when considering the introduction of rice into Japan:

“Arguably, from its sociopolitical ramifications, no other historical event was as significant for the development of what is now known as the Japanese nation.” [1]

Using food as a tool to understand and explain culture is perhaps as old as the discipline of anthropology itself.[2] One of the key points that Ohnuki-Tierney probes is the assumption that rice, which is used as such a key signifier (internally and externally) of Japan and ‘Japan-ness’, is not Japanese at all (or not quite as Japanese as presumed). This is not such a surprise when examining other foods that are now seen as “Japanese”: such as ramen (from China) or tempura (from Portugal). But ahead of all other dishes rice is promoted as uniquely Japanese. What rice offers is an important tool to reinforce a broader narrative of homogeneity. Japonica rice (Oryza sativa subsp. japonica) is one of two major, domestic rice types found in Asia. Despite the name, Japonica rice was first domesticated in China, along the Yangtze River basin around 9,500 to 6,000 years ago.[3] It is much later, around 350 BC that wet-rice agriculture is introduced to Japan, arriving (like most Chinese imports) to Kyushu via the Korean Peninsula.[1] Ohnuki-Tierney notes that even despite nearly 2,000 years of wet-rice agriculture this type of farming was not adopted across the population (or Japanese islands) to make up a universal “staple” food in the nation.

Despite this, for many Japanese it did become not just the staple food but it also developed into currency (and therefore status). Once a specialty crop for elites, rice agriculture spread north up from Kyushu. In Edo Japan, under the Tokugawa shogunate, the Kokudaka rice system was used for local lords to tax those working on their land (A koku, the unit of rice taxed, is even a Chinese measurement). Rice became money. If you have ever visited a historic Japanese farmhouse from this time, particularly of a wealthy landowner, you will find an entire room or storehouse with large, heavy safe doors. These spaces, known as kura, are the bank accounts of their day. Designed to hold the wealth of the family safe. As rice became a symbol of status, so too did the increasingly elaborate and fortified kura. Such was the attraction of rice as “pure money” that even after metalic currency was introduced in the 16th century the barter (rice-based) currency system returned in the 17th century as farmers preferred it to manage the payment of their taxes. [1]

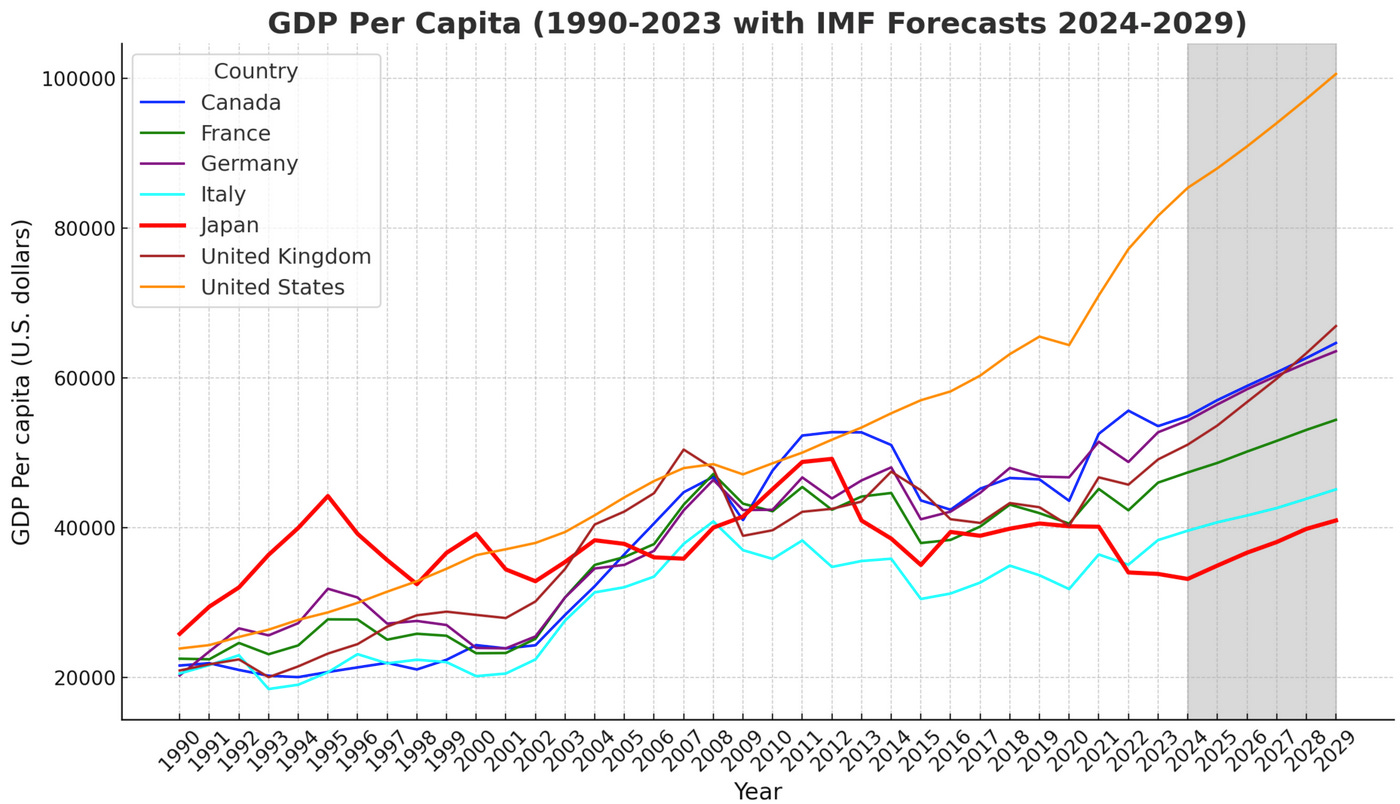

As previously noted, Ohnuki-Tierney’s book is positioned at a key moment in Japanese identity: completed in 1992 this is the same year that the Japanese price bubble burst. Japan’s rapid economic miracle and ascendancy on the world stage is over. What will follow is – at the time, optimistically – known as “The Lost Decade”. As Japanese economic stagnation continued beyond the 1990s this became The Lost Decades, first in 2000s, then into 2010s. Rice was no longer “pure money” currency but around the same time of Japan’s economic concerns, the stability of rice as identity was being called into question. Crucially: if rice is not Japanese. Can it still be a symbol of Japan?

Source [4]

What makes Japanese rice Japanese?

One of the key pillars propping up rice as such a powerful marker of identity was not just the strain (Japonica: short grain rice over long grain more common in other parts of Asia) but also the strict rules prohibiting rice imports. This meant that rice was not only Japanese in its “origins” but also its source. Here we need to understand how rice was (and largely still is) produced and managed in Japan.

Unlike mass-industrialised agriculture, which can be found across other parts of Asia and the West, rice in Japan is predominantly produced by smallholders. The average rice farm in Japan is around 1.5 acres.[5] A large number of these farmers do this work part time. Importantly, under the Staple Food Control Act of 1942, the Japanese government is formally in charge of all rice production, distribution, and sales. In order to manage the price of Japanese rice many rice field owners are paid subsidies to not produce rice at certain times. This system, known as gentan, was designed to support farmers while massive import tariffs were placed on imported polished rice.[6]

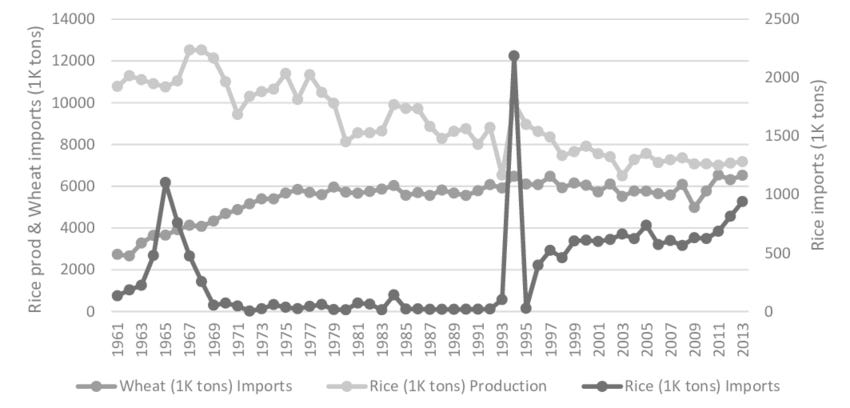

In the late 1980s Japan came under increasing pressure to import rice from the United States. The rice, farmed in California, was identical to the Japonica strain grown in Japan, but was seen as totally alien. It was Japonica yet not Japanese. Both rural Japanese and urbanites (who largely footed the bill in both high prices and tax to support subsidies) were opposed to it. But then Japanese crops failed. A 1993 headline in the LA Times reads like a telegram from the past: “Crop a Disaster, Reluctant Japan to Import Rice.”[7] This resulted in not just a giant spike (see table below) to secure the supply in the moment but also helped to open the door to steady imports from (primarily) The United States and Thailand. While the door is open, heavy tariffs remain. In 2013 import tariffs for polished rice reached 777.7%.[6]

Source [8]

The import of Californian rice was an event to grab headlines but it actually helped to question the idea of “Japanese” rice. As Ohnuki-Tierney says:

“The Representation of the entire nation as “agrarian Japan” denies the heterogeneity of Japanese society through history by portraying the Japanese as a monolithic population consisting entirely of farmers.” [1]

Rather than simply destroying held notions of identity in Japan, it opens up a wealth of other Japanese identities (as well as foods to taste). It is here that our friends – the mountains – show their hand. The fact that both Japan is scattered with mountains and made up of islands has enabled regional Japanese food, rather than one, homogeneous “Japanese Food” to be so rich in diversity of flavour, texture and preparation.

“Topographical factors were especially important: people who lived on the plains, in the mountains, or along the seacoast ate the plants that grew there; therefore, their reliance on specific foods, especially rice, differed.” [1]

Regional foods have always been important in Japan. The kyōdo ryōri of each area are proudly boasted at train stations or shared when meeting friends from different regions. Whether this is the tiny bowls of wanko soba from Morioka or Hiroshima’s salty dote-nabe soup pots, chests will puff up as locals announce the best place to experience a delicacy linked with their land (or sea).

Alongside this enduring theme, Japan has also been taken by an increased global interest in wild foods. In Japan sansai (wild plants) can now be found at eye watering prices in the boutique Takashimaya supermarkets in Tokyo. Once viewed as the diet of the poor (and what many rural Japanese sustained themselves with during wartime poverty) these ingredients have become popular again. High profile chefs, such as Yoshihiro Imai of Kyoto’s Monk restaurant, have helped to elevate foraged foods to delicacy items. The experience of exploring the land has also become popular and a driving force for people visiting rural areas, and the mountains.

It’s for this very reason I find myself in Ishikawa, on the West Coast of Japan. Visiting friends in the area I am invited to join a foraging tour, which is run by the local residents for tourists. It’s very popular. Our tour is run by Yamashita-san. A smiling octogenarian who barrels off wisdom in short shots and then disappears into bushes, beckoning us to follow. “My name is Yamashita-san. I live at the bottom of the mountain. It was fate.” He jokes. Yama means mountain and shita means below. And then he’s off again. “Watch out for snakes.” He says cheerfully. “There are loads in this area.” We look at his sturdy boots. Then down at our canvas shoes. He’s already climbing the next hill. We leapfrog from plant to plant. Each one encouraged into our mouths, with barely enough time to savour before rushing on. Curled warabi fiddle heads hide in the fields and tangy sansho pepper pods poke out from the side of the road. We follow his pink hat through the bushes. Each time comes a name, a guess at the English translation and a guide on how to eat it. As we walk Yamashita-san points out the Gentan fields lying dormant. Tangled with weeds. high above a Black Kite is circling.

After an hour of tasting, note-taking and fumbled translations everyone is exhausted, except Yamashita-san. He bids us farewell and leaves us at our farmhouse to enjoy the local sansai with, what else: a bowl of rice.

Thanks for reading. Wherever you are, stay safe and see you in the mountains.

Stu

Rice as self, Ohnuki-Tierney, 1993

Food Culture: Anthropology, Linguistics and Food Studies (link)

Archaeological and genetic insights into the origins of domesticated rice (link)

Table: The Lost Decades, Wikipedia (link)

Rice: It's More Than Food In Japan (link)

Political staple, Economist (link)

Crop a Disaster, Reluctant Japan to Import Rice : Agriculture: California’s 2,500 growers should benefit by $100 million. But this is not an end to ban, Tokyo emphasizes. LA Times (link)

Table: Food self-sufficiency and food sovereignty: Examining the fallacy of the 'change in taste and preferences mantra' in the evolution of the Japanese rice system. (link)

*Ohnuki-Tierney does note in the preface that she made important additions in 1992 from a seminar at École des hautes études en sciences sociales.

Great stuff!